Table of Contents

- The Story of Hans

- Superpowers of Animals

- Theory of Mind?

- Can Structural differences depend on the environment?

- Conclusion

- References

The Story of Hans

The story of Clever Hans is a well-known tale in the field of animal behavior and cognition. It is often cited as an example of the need for careful consideration and methodology in studying animal intelligence.

For those unfamiliar with the story, Hans was a horse trained by Wilhelm Von Osten, a math teacher, to perform basic mathematical tasks. Through extensive training, Hans was able to demonstrate an understanding of addition, subtraction, and other mathematical concepts. When asked a question, such as "What is 2+3?", Hans would tap his hoof on the ground five times to indicate the correct answer.

This story serves as a reminder of the need for rigorous scientific methods in studying animal cognition. It highlights the potential for unconscious biases and errors in interpretation, and emphasizes the importance of careful experimentation and analysis in understanding the mental abilities of non-human animals

The news of Hans's abilities quickly spread throughout Germany, leading to the formation of a commission to examine his skills. The commission was headed by psychologist Carl Stumpf, who believed that Osten was a fraud and that Hans's abilities were due to Osten's trickery. As a result, Osten was removed from Hans's line of sight during testing. However, Hans continued to correctly answer questions. Subsequently, psychologist Oskar Pfungst from the University of Berlin was called in to conduct further analysis.

Pfungst removed the questioner from Hans' line of sight, which resulted in the horse experiencing difficulty in answering questions. It became clear that Hans was receiving some form of information. Pfungst conducted a thorough experiment to determine the source of this information. The results indicated that Hans was not looking at the blackboard or listening to his owner's questions. Instead, he was picking up on unconscious cues from the owner, such as slight movements in their head or eyebrows. If the questioner could not see the question on the blackboard, Hans would continue to search for a cue that never came. While Hans may have appeared to be clever, his abilities were actually derived from his ability to detect and interpret these subtle cues. He had learned to associate these cues with a reward in a complex situation.

|

|---|

| Hans, the horse who could do math |

Superpowers of Animals

The story of Clever Hans serves as a reminder to always approach claims of extraordinary animal abilities with skepticism. While it is clear that animals possess unique cognitive abilities, it is important to conduct thorough experiments and analysis in order to accurately discern the extent of these abilities. The lack of clear environmental parameters and a defined baseline of normal behavior in many videos depicting "unusual animal behavior" make it difficult to accurately assess the true abilities of the animal in question. It is important for researchers to take these factors into consideration in order to avoid the pitfalls of the Clever Hans phenomenon.

It is well known that laboratory experiments often provide more controlled conditions for examining animal behavior, leading to clearer insights into their cognitive abilities. However, even in these highly controlled settings, it is important to remain cautious about making sweeping conclusions about animal cognition. This is exemplified by the case of Clever Hans, a horse whose apparent ability to perform complex mathematical calculations was later revealed to be a result of his ability to pick up on unconscious cues from his human questioner.

In a similar vein, the work of Inoue and Matsuzawa (2007) on chimpanzees' working memory capabilities has garnered significant attention. Their experiments seemingly demonstrated that young chimpanzees possess an extraordinary ability to recall numerical information, outperforming human adults. However, it is worth noting that the human participants in the study did not receive the same level of training as the chimpanzees. Despite this, Inoue and Masuzawa concluded that their findings align with our understanding of eidetic imagery in humans. Our study shows that young chimpanzees have an extraordinary working memory capability for numerical recollection better than that of human adults. The results fit well with what we know about the eidetic imagery in humans.

It is essential to approach such findings with skepticism and to carefully consider the implications of our conclusions. As always, further research is needed to fully comprehend the cognitive abilities of non-human animals.

After 3 years, another study was conducted by Cook and Wilson (2010). Their results indicate that when human participants are trained to the same extent as Matsuzawa's chimpanzees, they outperform chimpanzees in terms of accuracy (with 93% and 97% accuracy). In conclusion, the impressive working memory performances of chimpanzees can be explained by their extensive training. Ayumu (one of the chimpanzees in Matsuzawa's study) excelled due to rigorous training sessions. However, some have argued that Ayumu may have possessed unique abilities. Humphrey (2012) hypothesized that Ayumu outperformed humans because he had synesthesia (a neurological trait that results in the merging of senses that are not normally connected, such as associating numbers and faces with colors). In my opinion, this is a compelling explanation and may be true. However, there is currently no robust evidence to support this hypothesis.

It is crucial to approach findings regarding the cognitive abilities of non-human animals with skepticism and to carefully consider the implications of our conclusions. As always, further research is needed to fully understand the complex nature of animal cognition.

Theory of Mind?

One example of a controversial topic in the field of animal cognition is the theory of mind, which refers to the ability to understand and predict the goals and intentions of others. The idea that chimpanzees possess a theory of mind has been widely discussed, with some researchers positing that they are able to represent behavior not simply as "he takes the banana" but also as "he intends to eat the banana." However, the problem with making such claims is that it is nearly impossible to know the mental states of animals, as we cannot ask them directly about their intentions or motivations. As such, our explanations of animal mental states are often based on observed behaviors, which can be subject to interpretation and bias. While it is possible that chimpanzees possess a theory of mind, it is important to recognize that such a conclusion ultimately requires a discussion of consciousness, which is a complex and contentious topic.

|

|---|

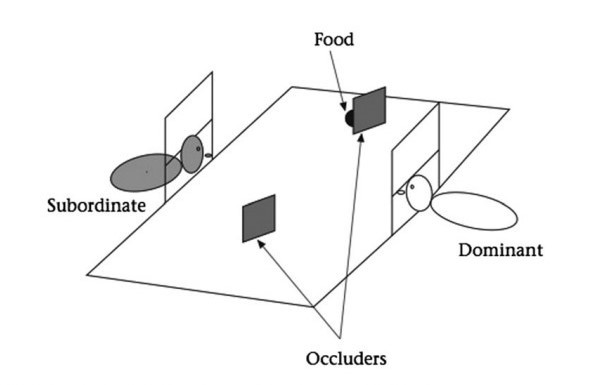

| Fig 1: A famous experimental method was conducted by Hare et al., 2001 (image taken from Hare et al. 2001). Hare has used chimps’ strategies for the food competition. In this experiment, the non-dominant chimp and dominant chimp were released into a room that has food, via two doors across from one another. The food was hidden by experimenters however non-dominant chimp was always know the exact place of the food but it was not known by the dominant chimp. Since a non-dominant chimpanzee is not allowed to take food from a dominant chimpanzee, the non-dominant chimp is reluctant to approach food. The results were clear: the nondominant chimpanzees avoided food that the dominants could see. Thus, they concluded that chimpanzees understand others’ perceptual states. |

Some researchers have claimed that chimpanzees possess a theory of mind, while others have disputed this claim, offering alternative explanations for their behaviors. For example, Call and Tomasello (2008) have argued that chimpanzees have a theory of mind and that their behavior can be interpreted as representing not just actions, but also intentions. However, Povinelli and Vond (2003, 2004) and Penn (2008) have suggested that chimpanzees may be able to read behaviors rather than minds, based on their experiences with feeding behaviors and the consequences of approaching food in the presence of dominant individuals.

The debate over the existence of a theory of mind in chimpanzees highlights the complexity of studying animal cognition and the need for careful examination of experimental methods and findings. Further research is needed to fully understand the cognitive abilities of non-human animals.

It is important to approach findings about animal cognition with skepticism, and to consider the potential limitations and alternative explanations of such findings. As the story of Clever Hans illustrates, the perception of animals' mental states can be easily influenced by our own biases and assumptions. We must be vigilant in avoiding the pitfalls of anthropomorphism and seek to understand animal behavior in a rigorous and scientific manner. To this end, it is crucial to carefully consider potential "killjoy explanations" when studying animal cognition, in order to avoid overstating the capabilities and mental states of non-human animals (Shettleworth, 2010).

Can Structural differences depend on the environment?

The structural differences between laboratory-born and wild-born animal subjects can have a significant impact on our understanding of animal cognition. In a recent study, Janmaat (2019) highlighted the importance of considering brain plasticity, or the brain's ability to adapt and change in response to environmental factors. This is especially relevant when comparing the cognitive abilities of laboratory-born and wild-born animals, as their living conditions may vary greatly. Janmaat's study also found that while captive-based studies were cited more often than field-based studies, field-based studies were more balanced in their citations. This suggests that comparing the cognitive abilities of animals in their natural habitats to those in captivity can provide valuable insights into the evolution of cognitive abilities. Overall, it is crucial to approach studies of animal cognition with a robust methodology and a consideration of the potential biases and limitations of our findings.

In 1970, Gallup (1970) conducted a pioneering study to determine whether chimpanzees possess the cognitive ability of self-recognition. In this study, chimpanzees were first exposed to a mirror for several days. Afterwards, while under anesthesia, the chimps were marked with dye. After recovering from the anesthesia, the chimps were observed to touch the marks more frequently when a mirror was present than when it was absent. This mirror touch test is often taken as evidence of self-awareness or recognition. However, I believe that this method is not particularly robust when applied to animals. When we look in the mirror, we see our own reflections and we understand that the image is a representation of ourselves. However, we cannot assume that animals have the same cognitive process. This idea is based on our own assumptions and, as such, the mirror test is not a reliable way of determining self-awareness in animals. Povinelli (2000) suggests that chimpanzees may see the reflection in the mirror as a "strange object" that they are able to manipulate through their own movements. Therefore, it is possible that, although chimpanzees can detect marks in mirrors, they either do not understand the image to be a representation at all, or they understand it to be a representation of a body that they do not have any emotional connection to. Therefore, the mirror task does not necessarily involve a higher-order self-representation process.

It is worth noting that subsequent research by Gallup (1971) utilized laboratory-born chimpanzees that were raised in isolation from an early age, and failed to demonstrate self-recognition when subjected to mirror tasks. This finding supports the notion of brain plasticity, as highlighted by Janmaat (2019), and suggests that the environment in which an animal is raised can greatly impact its cognitive abilities. Furthermore, the failure of these laboratory-born chimpanzees to exhibit self-recognition in mirror tasks calls into question the validity of using such methods to assess self-awareness in non-human animals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while animal behavior research is crucial to understanding the cognitive abilities of non-human animals, it is important to approach such findings with skepticism and to carefully consider the implications of our conclusions. The use of rigorous methodologies and a willingness to consider alternative explanations, or "killjoy" explanations, can help ensure that our understanding of animal cognition is grounded in robust evidence. Moreover, the consideration of factors such as brain plasticity and the differences between laboratory-born and wild-born animals can provide a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of animal cognition. Further research is needed to fully explore these complex issues.

References

Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2008). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? 30 years later. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(5), 187–192. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.010

Cook, P., & Wilson, M. (2010). Do young chimpanzees have extraordinary working memory? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 17(4), 599–600. doi:10.3758/pbr.17.4.599

Gallup, G. G. (1970). Chimpanzees: Self-Recognition. Science, 167(3914), 86–87. doi:10.1126/science.167.3914.86

Gallup, G. G., McClure, M. K., Hill, S. D., & Bundy, R. A. (1971). Capacity for Self-Recognition in Differentially Reared Chimpanzees. The Psychological Record, 21(1), 69–74. doi:10.1007/bf03393991

Hare, B., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2001). Do chimpanzees know what conspecifics know? Animal Behaviour, 61(1), 139–151. doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1518

Humphrey, N. (2012). “This chimp will kick your ass at memory games — but how the hell does he do it?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(7), 353–355. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.05.002

Inoue, S., & Matsuzawa, T. (2007). Working memory of numerals in chimpanzees. Current Biology, 17(23), R1004–R1005. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.027

Janmaat, K. R. L. (2019). What animals do not do or fail to find: A novel observational approach for studying cognition in the wild. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. doi:10.1002/evan.21794

Penn, D. C., Holyoak, K. J., & Povinelli, D. J. (2008). Darwin’s mistake: Explaining the discontinuity between human and nonhuman minds. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31, 109–178.

Povinelli, D. (2000). Folk physics for apes. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Povinelli, D. J., & Vonk, J. (2003). Chimpanzee minds: Suspiciously human? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 157–160

Shettleworth, S. J. (2010). Clever animals and killjoy explanations in comparative psychology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(11), 477–481. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.07.002

Cite:

Altun, E. (2021, April 19). Theory of Mind and Other Controversies in Animal Cognition Research. Retrieved from https://altunenes.github.io/posts/animals/