Table of Contents

- Background

- What is Spatial Frequency and Coarse-to-Fine Theory?

- How LLMs see illusions

- The Experiment

- Conclusion and Final Thoughts

Background

Seeing faces in inanimate objects —a phenomenon called pareidolia— is a common human experience. With today's powerful Vision-Language Models (VLMs), a simple question arises: do they see these illusory faces too? Probing their "vision" this way isn't just a fun experiment. It's a practical way to understand their inner workings, challenge our assumptions when building with them, and explore the gap between artificial and biological sight.

This question grew out of my master's research, where I used EEG to study how the human brain processes these very illusions, which led to an ERP paper on the topic.

What is Spatial Frequency and Coarse-to-Fine Theory?

So, how do you fairly test an AI's perception? My plan was to see if it falls for the same visual shortcuts our brains do.

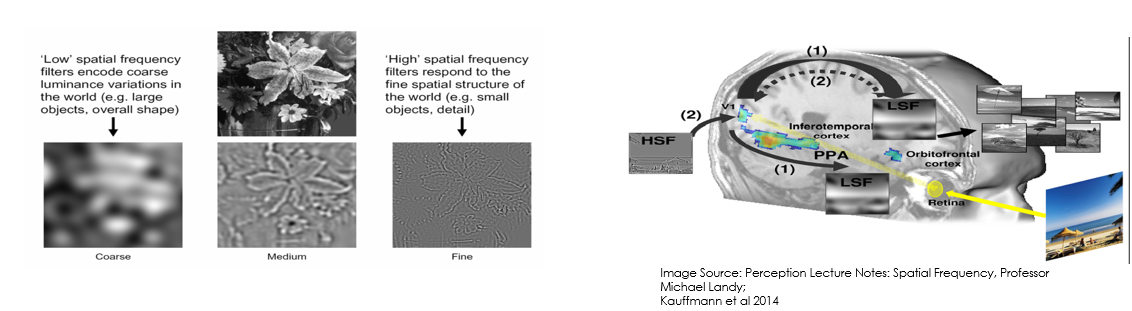

This is based on a key idea in human vision called the Coarse-to-Fine theory. In short, human brain processes the blurry, general, coarse, "gist" of something first, and then uses that initial guess to figure out the finer details more quickly. The technical way to separate the "gist" from the "details" is with spatial frequencies, which can be isolated using techniques like 2D Fourier filtering.

- Low Spatial Frequencies (LSF) are the blurry, large-scale shapes.

- High Spatial Frequencies (HSF) are the sharp edges and fine textures.

You experience this all the time. Think about recognizing someone from across the street—you see their overall shape long before you see their eyes. While not about spatial frequency directly, a study on hierarchical processing shows a similar "general first" principle: people can spot an animal in an image in just 120ms, but need longer to identify it as a dog (Wu et al., 2014).

My whole experiment was designed around this: would the AI also see a face in the blur, but get confused by the sharp details? To test this, I needed to isolate these frequencies.

|

|---|

| Visualizing the Coarse-to-Fine theory. The left shows an image broken into coarse (Low Frequency) and fine (High Frequency) information. The right shows how the brain processes the coarse 'gist' first to guide perception. |

To do this, I used a Butterworth filter from my own Rust tool, which you can try out here: butter2d.

How LLMs see illusions

Research shows that modern VLMs are not objective, infallible observers; they can be "fooled" by classic visual illusions, and their susceptibility often increases with model scale Shen et al., 2023 . This suggests they are learning statistical heuristics from their training data that mimic human perception, rather than developing a deep, structural understanding of the world.

This makes pareidolia a particularly interesting test. It's not a geometric trick, but an illusion driven by a powerful, top-down, and likely evolutionary bias to find faces in our environment.

The Experiment

To test how Gemini handles pareidolia, I took several images and created three versions of each (using butterworth filter): the original Broadband (BB), a blurry Low Spatial Frequency (LSF) version, and a sharp-edged High Spatial Frequency (HSF) version. I then fed them to the model with a simple prompt. To avoid any "memory" or context-priming effects, each images was processed in a completely separate session.

Here was the prompt:

"What are the three most prominent objects you see in this image? Respond in a JSON format where each object has a 'name' and a 'confidence_score'."

Here are the results.

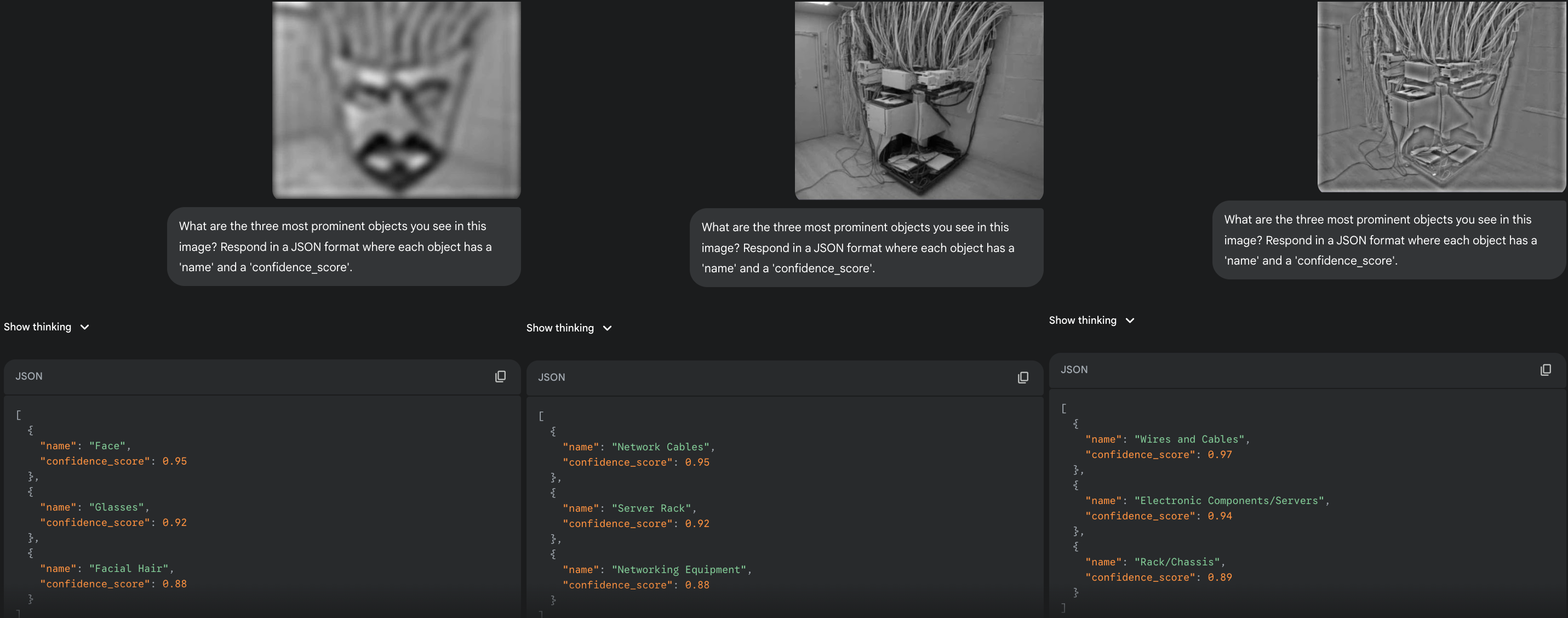

Test 1: The Wire Face

This image of server cables, which I found on X (formerly Twitter), has an uncanny facial structure. As hypothesized, the LLM completely missed the face in the broadband and HSF versions, describing only the literal content. However, when presented with the LSF version, where only the coarse, global shape remains, it immediately and confidently identified a "Face". So the fine HSF details of the wires and components seem to break the illusion for the model, while the blurry LSF version provides the ideal template for a face.

|

|---|

| LSF (left), Broadband (middle), HSF (right) versions of the 'Wire Face'. |

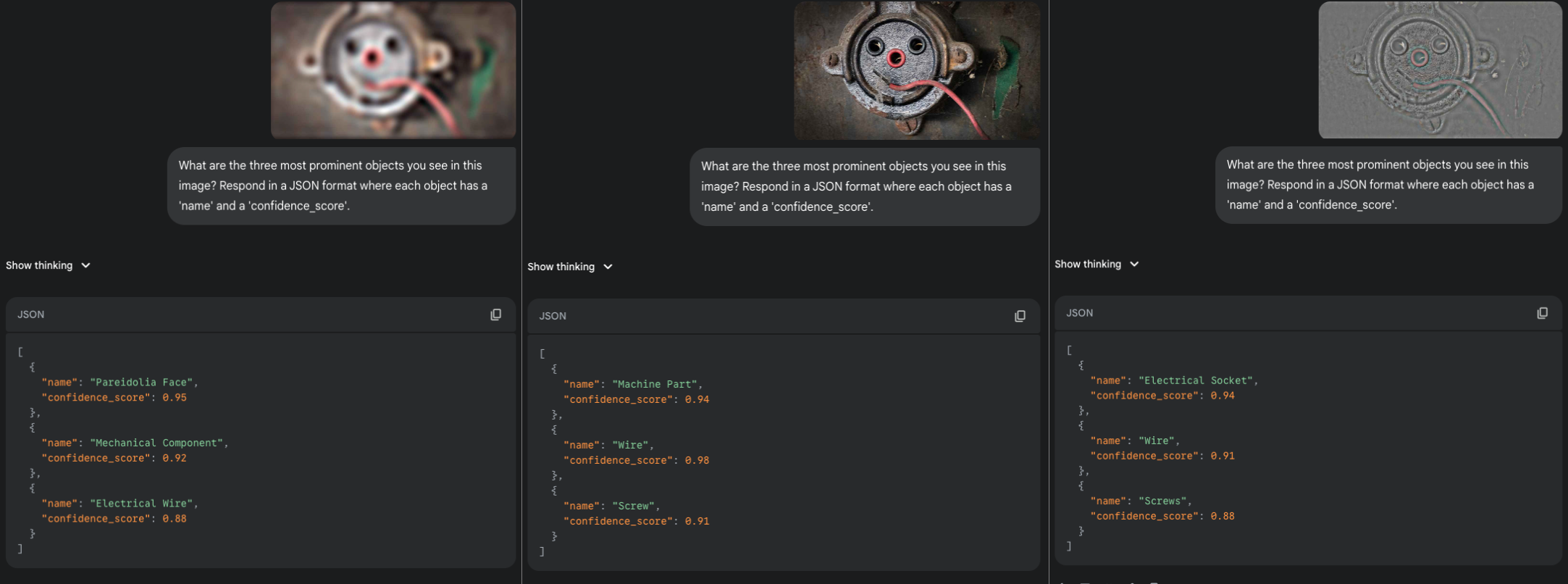

Test 2: The Church Face

Next, I used one of the most famous pareidolia images on the internet. My rationale was that if the model's perception is purely a function of its training data, it would have surely seen this image and would recognize the face (or illusory face). Once again, it failed to see the face in the BB and HSF versions, focusing only on the architecture. But in the LSF version, it correctly identified a "Face (Pareidolia)". This suggests the model's failure isn't just about a lack of training data. The high-frequency details of the building's facade actively mask the illusion for the AI, even for a classic example.

|

|---|

| The famous 'Church Face' pareidolia. Note that the model only sees a "Face (Pareidolia)" in the LSF version, describing only architectural elements in the others. |

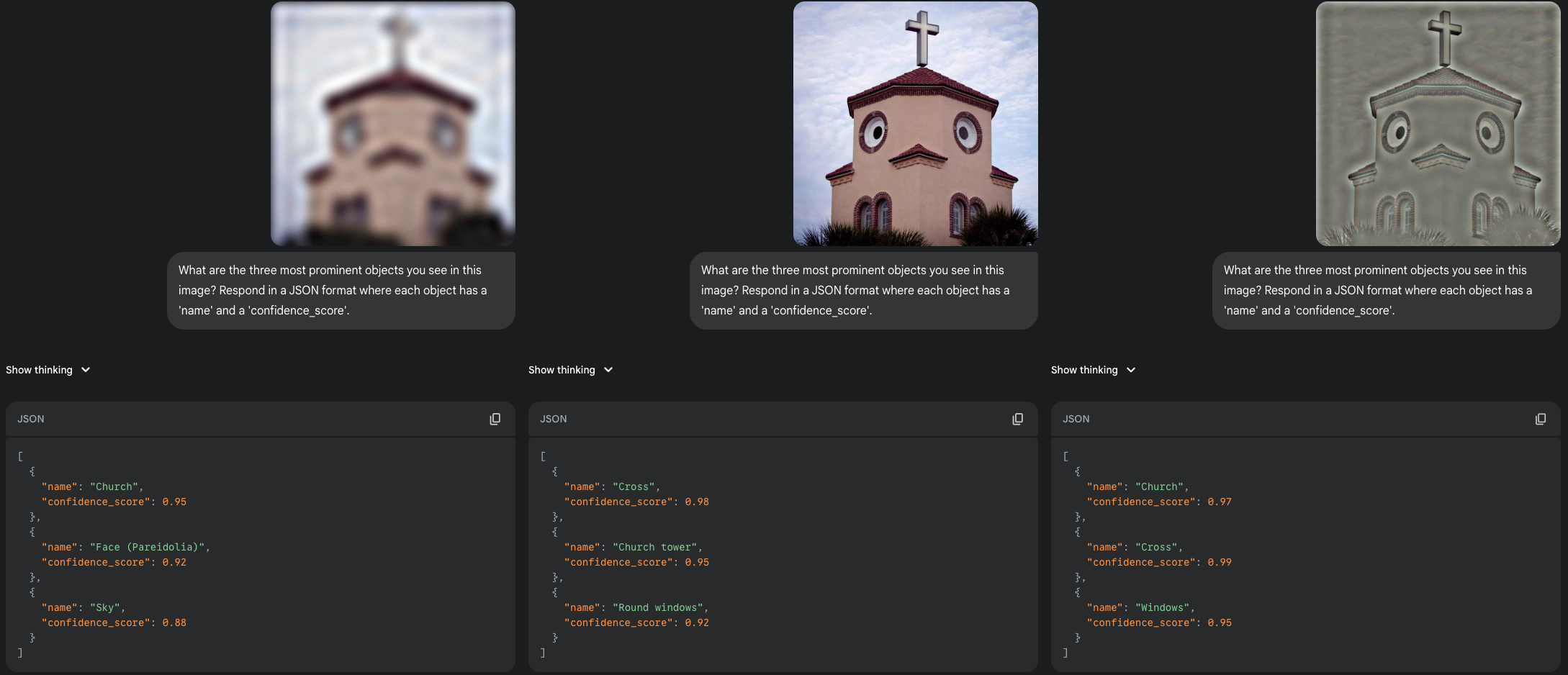

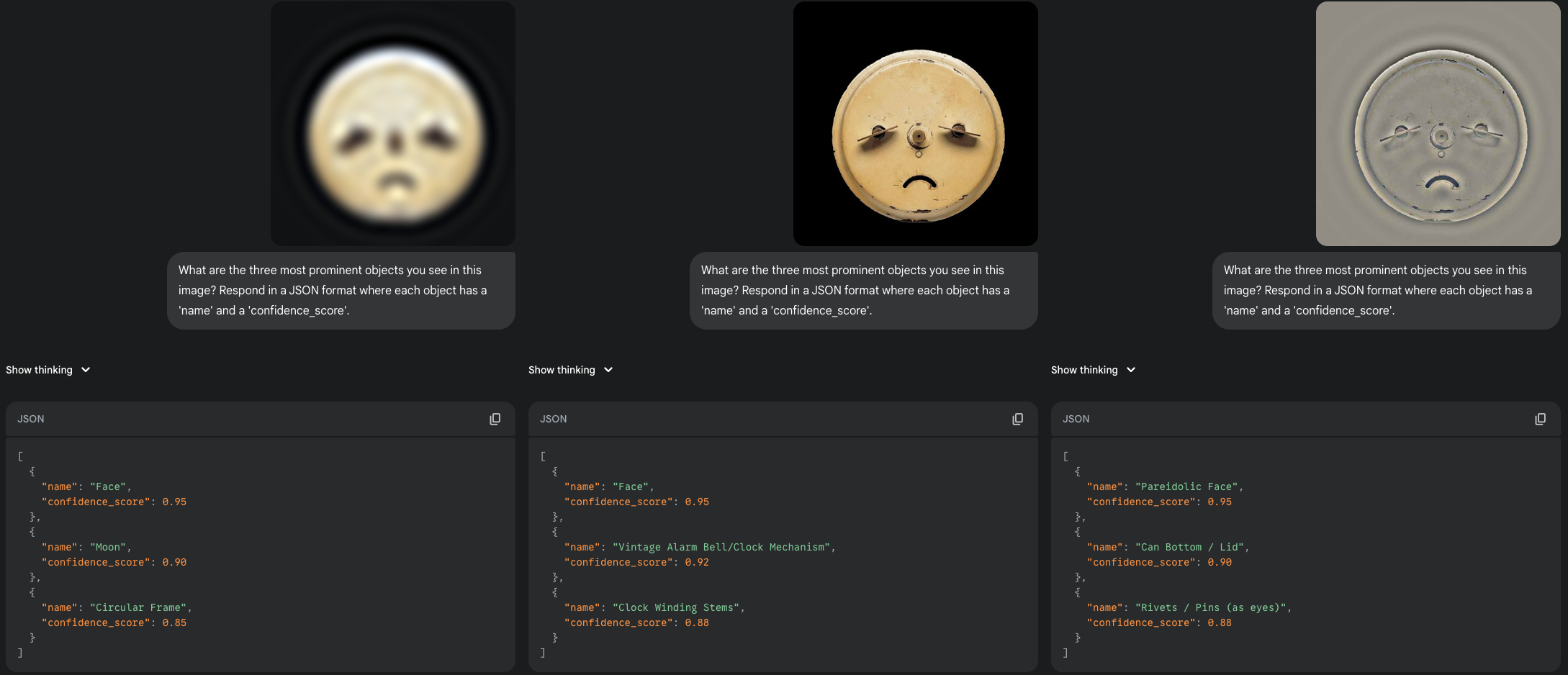

Test 3: The Oval Hypothesis

The previous results sparked a new idea: perhaps the LLM's internal "face template" is strongly biased towards the oval, rounded shapes of human faces? The "Wire Face" is very angular. To test this, I selected two images with a more circular structure.

The first, an electrical component, followed the now-established pattern. A "Illusory Face" was detected in the LSF version, but the BB and HSF versions were seen only as literal machine parts.

|

|---|

| An illusory face in an electrical component. The LSF version triggered a "Pareidolia Face" detection, while the detailed versions only yielded descriptions of machine parts. |

The second image, however, gave a breakthrough result. This time, the LLM saw a face in all three versions! It identified a "Face" in both LSF and BB, and even a "Illusory Face" in the sharp HSF image. This is a brilliant finding. It suggests that when an object's structure is a strong enough match for the AI's internal face template (a round shape, two distinct "eyes," a "mouth"), it can overcome the distracting HSF noise. This is also highly consistent with human vision, where HSF information is vital for analyzing the fine features of a face once it has been detected.

|

|---|

| A illusory face on a can or clock mechanism that the LLM saw in all versions. |

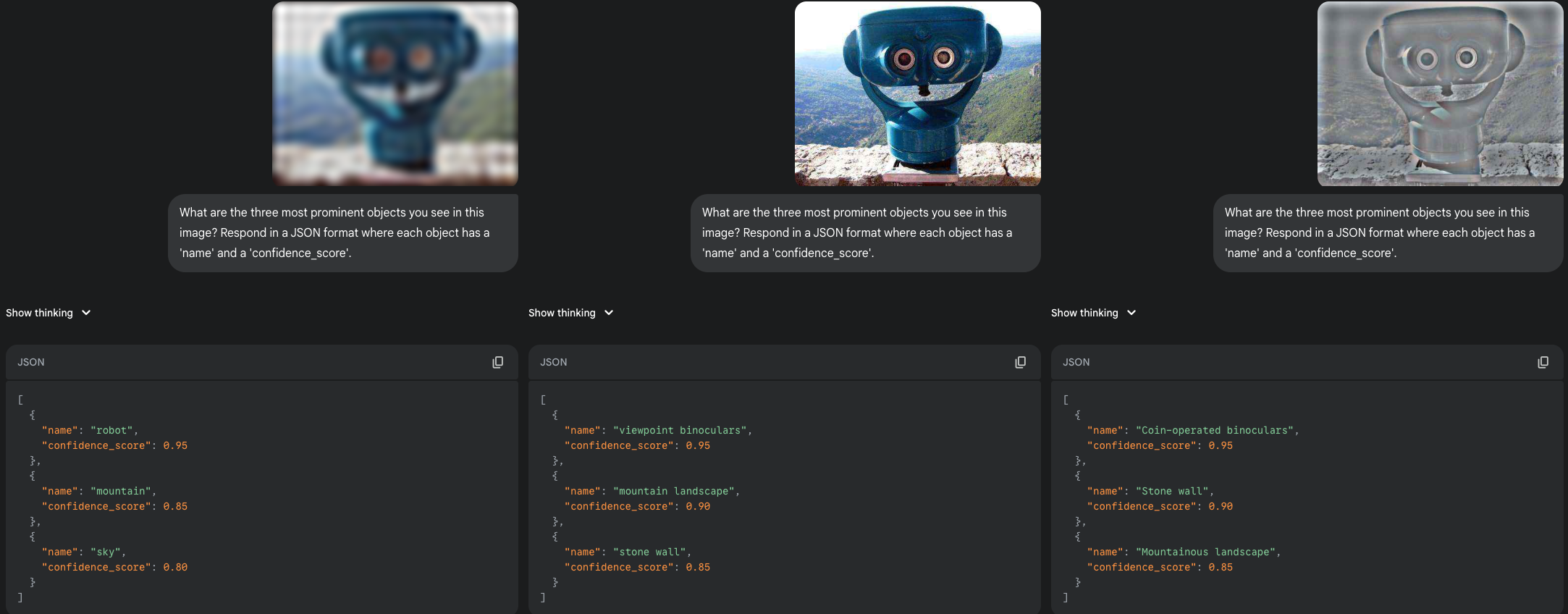

Test 4: The Illusory Robot

This next test uses a common object that happens to have face-like features: a set of viewpoint binoculars. The results show another interesting form of interpretation by the model. In the LSF version, the blurry shape with two prominent circles triggers an anthropomorphic classification: "robot". The model defaults to a familiar humanoid template. However, once the HSF details are available in the broadband and sharp versions, the model corrects its initial "guess" and accurately identifies the object as "viewpoint binoculars".

|

|---|

| An LSF-induced "robot" is corrected into binoculars with more detail. |

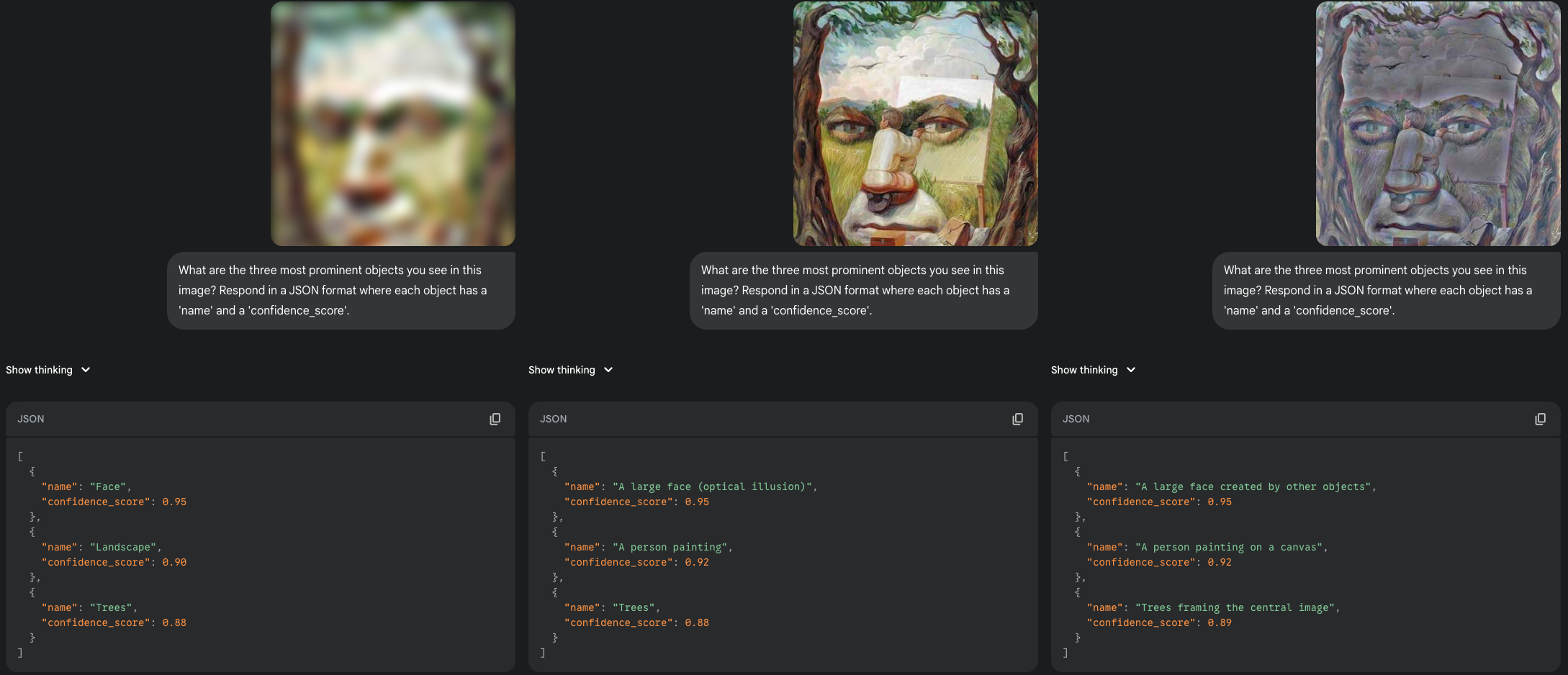

Test 5: The Holistic Face Paintings

Finally, I moved from pure pareidolia to a different kind of illusion: composite portraits, famously painted by artists like Giuseppe Arcimboldo. In these images, the face is intentionally constructed from other objects. These aren't really pareidolia in the same way; they are deliberate artistic constructions where recognizing the face requires holistic processing—seeing the overall arrangement rather than just the sum of the individual parts. How would the LLM fare?

The first painting is a face constructed from a landscape. Interestingly, the model identified a "large face" in both the broadband and high-frequency versions. This is a departure from the earlier pareidolia examples. Here, the individual components (trees, rocks) don't look like facial features on their own, but their careful arrangement creates a powerful holistic impression that the model was able to perceive, even with all the fine details present.

|

|---|

| A composite face, testing holistic perception. Notably, the model identified the face in all three versions, even describing it as an 'optical illusion' in the BB. |

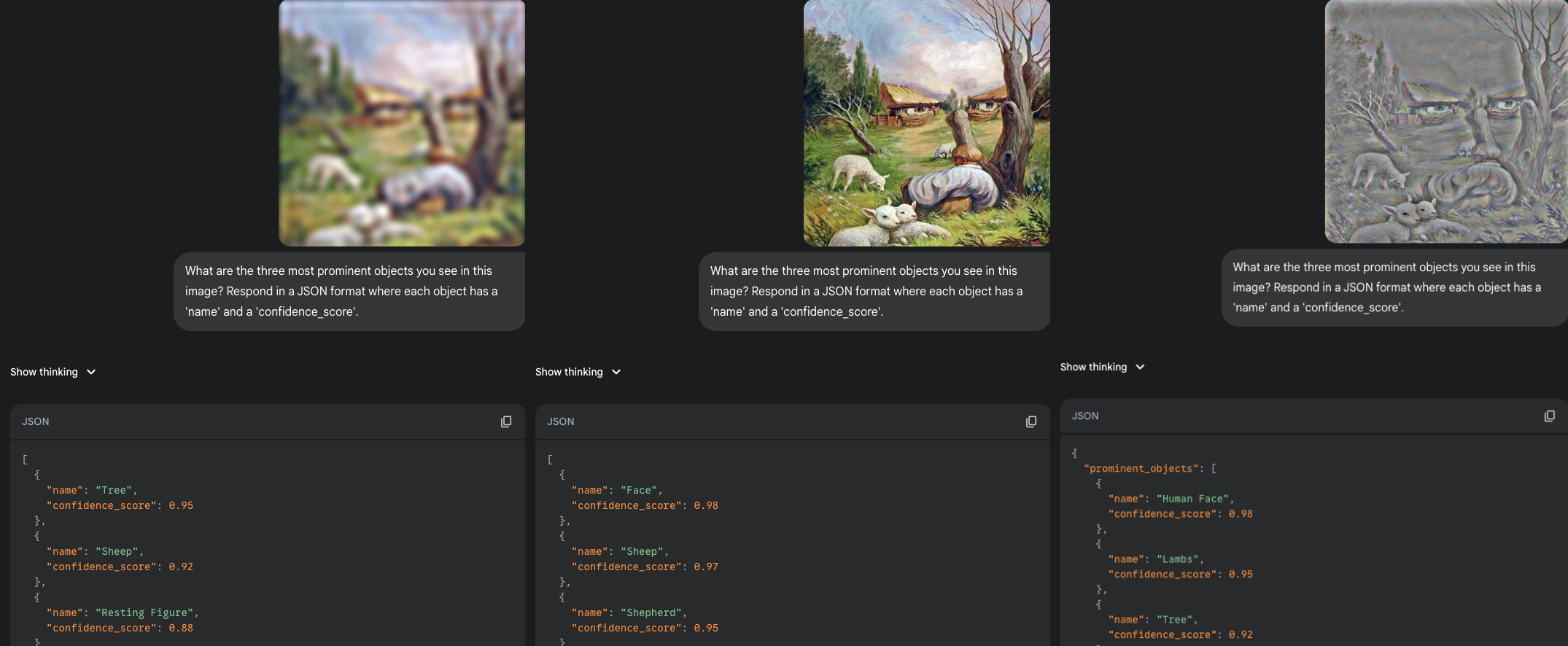

I tried a second, similar painting of a shepherd in a landscape forming a face. The results were just as intriguing. In the full-detail versions, the model successfully identified both the whole ("Face") and the parts ("Sheep", "Shepherd"). It seemed to parse the image on multiple levels simultaneously.

However, an interesting twist occurred in the LSF version. The blur, which helped reveal faces in the pareidolia examples, seemed to weaken the illusion here. The model's top guess for the LSF version was "Tree", not "Face". This might suggest that for these complex, deliberately constructed images, the precise arrangement and HSF details are actually critical for the holistic face to emerge, and blurring them can break the carefully crafted composition. It's a fascinating case where the general rule (LSF reveals faces) is reversed, highlighting the complexity of both human and machine perception.

|

|---|

| Another composite face, where blur seemed to hinder, rather than help, perception. |

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

For anyone working with or building on top of these AI systems, I believe understanding these kinds of behaviors is important. An AI's failure to see a pattern that is obvious to us—or its tendency to see one only under specific conditions like blurring—highlights the inherent differences in how they process visual information.

This method of probing with spatial frequencies and illusions could serve as a simple, fun, intuitive benchmark for tracking the progress of future vision models. As new architectures are developed, seeing how they handle these edge cases can tell us a lot about whether they are developing more robust, human-like perception or simply becoming better at pattern-matching their training data.

Of course, there are clear limitations here. I only used one model, Gemini 2.5 Pro, primarily because company I work provides free access to it. Other powerful models from OpenAI, Anthropic, or elsewhere might react to these images in completely different ways. The number of images was also small.

Also you might be realized that model's own distinction between a "Face" and a "Pareidolia Face". What is the difference? When the model uses the simple "Face" label, does it believe it's seeing a real person or animal? Is the "Pareidolia" tag an admission that it recognizes the illusion?

Perhaps the most important takeaway is the value of using novel stimuli. The real test for these models isn't showing them the famous "Church Face" again, but presenting them with the new, illusory faces we discover in our daily lives—a pattern in a coffee stain, the front of a new car, or a strangely-shaped vegetable. These "wild" pareidolia images, which the AI could not have been trained on, are the truest test of whether they are learning to see or just to recognize. And for me, that's an experiment that never gets old.

Cite:

Altun, E. (2025, June 22). How LLMs See Illusory Faces. Retrieved from https://altunenes.github.io/posts/pareidolia/